This is the desk on which I wrote my Masters dissertation more than thirty years ago. I had a friend with a word processor who typed it up for me – that’s how much things have changed. I had very poor typing skills and no computer skills at all, and honestly thought that computers would have no impact on my life in any way.

Anyway, this desk was bought with my very last salary as a teacher, and sat in a corner, bruised and battered and looking very neglected. During lockdown 2 I finally sanded and varnished it and ordered a new insert which my husband put in for me, because my hands are too shaky for knives as sharp as all that. It will never look new, or even like a cherished antique, but it looks as though I love it, and I do.

This second phase of level 4 has been very hard, but in the way that mending a broken leg is hard. Tough as it is, it is possible to see strength and flexibility returning, recovering lost joy in free movement. Through it I have had to come to a deeper understanding of what inspires me, what I’m able to do, and, crucially, what I’m not. I had spread myself very thin, tried to follow so many different enthusiasms and causes, and battled with doubt and despair more than I allowed myself to notice. But this paring down of life and opportunity made me rest (goodness, that’s hard!) and look at where my heart is, the work that gives me satisfaction and joy, and how to deepen it so that I do it as well and as thoroughly as it deserves.

But it reminded me of how much love and joy there is in my life, in my kitchen, my garden, the territory of rain, in the writing about place and poetry that delights me, the friends who strengthen me and the people who so kindly tell me they like what I do. I feel a bit like my desk, sanded down a bit, and refurbished – made new.

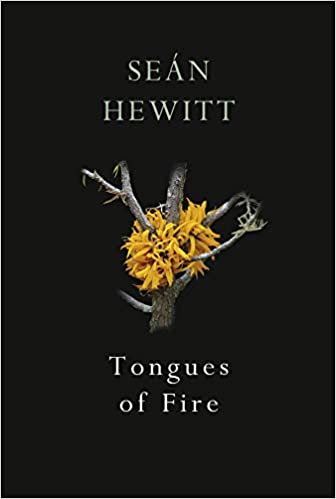

There will be new poetry next year – some of mine, and at least two new books by poets I’m excited to be working with, a fresh look for the newsletter (more of that later) and more reviews for the blog, and maybe a workshop or two. Plus territory pictures and herbs as usual, that isn’t stopping any time soon. I do hope you will join me!